129-Year-Old Vessel Still Tethered to Lifeboat Found on Floor of Lake Huron

The ‘Ironton’ has been perfectly preserved since the day it sank in ‘Shipwreck Alley’

Just off the coast of the northeast Michigan mainland sits the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. The area also goes by another, less benign name: “Shipwreck Alley,” the final resting place for over 200 ships tossed about by the fierce winds of the mighty Lake Huron. Finding sunken vessels is not uncommon here.

However, when researchers located a barely damaged 150-year-old schooner barge sitting on the lake’s floor, they made some waves.

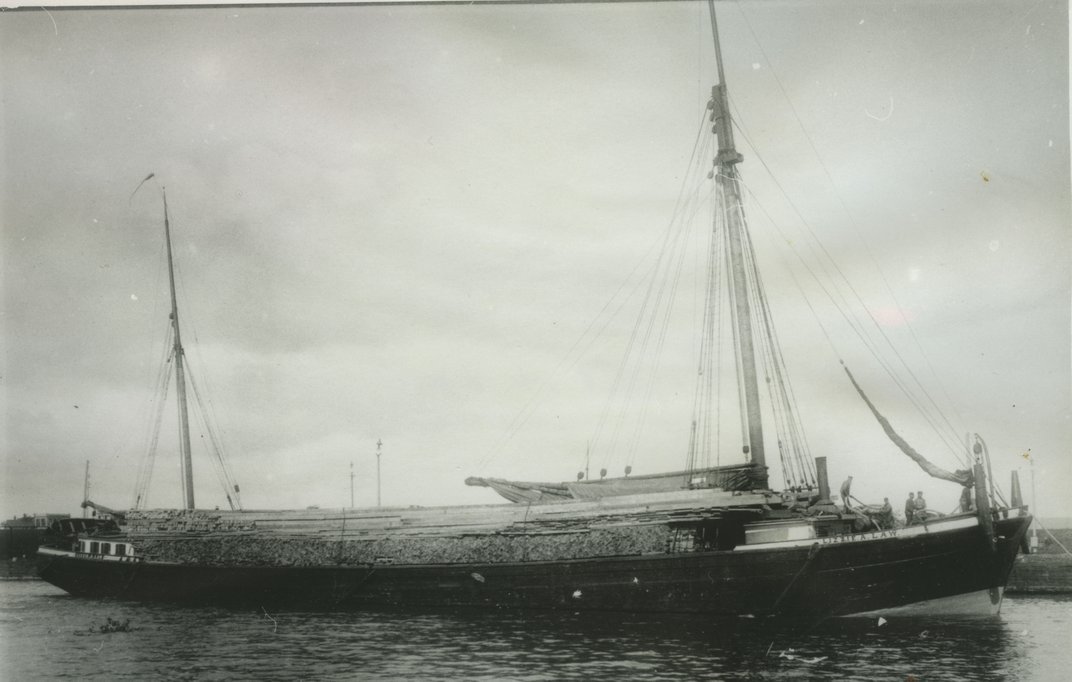

News of the discovery of the Ironton, a 191-foot wooden vessel capable of carrying more than 48,500 bushels of grain, was announced in a March 1 statement from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Researchers located the wreck in 2019, but they wanted more time to study it before going public.

“We have not only located a pristine shipwreck lost for over a century, we are also learning more about one of our nation’s most important natural resources—the Great Lakes,” says Jeff Gray, superintendent of the marine sanctuary, in the statement.

The cold freshwater of the lake has kept the Ironton intact. According to Michigan Radio’s Jodi Westrick, an anchor is still connected to the ship, as are its three masts. In addition, a lifeboat remains tied to the vessel, a chilling reminder of how the ship’s demise played out on a harrowing night in 1894.

In September of that year, the Ironton and another vessel, the Moonlight, were heading towards the port city of Marquette, Michigan. Both ships were being towed by a steamer, “a common practice then, much as a train engine pulls freight cars on a railroad,” writes John Flesher of the Associated Press (AP). The steamer broke down, and harsh winds nearly pushed the two barges into their guide. The crew of the Moonlight cut the Ironton’s tow line, leaving the ship adrift a few miles north of Shipwreck Alley.

According to the AP, the Ironton veered off course and ran into the Ohio, a freighter loaded with 1,000 tons of flour. With a hole in its bow, the Ironton quickly took on water and tried to deploy its lifeboat. But nobody managed to untie the painter, the rope which tethered the lifeboat to the vessel.

The only two survivors managed to grab onto debris and stay afloat until a nearby boat rescued them; the other five crew members perished. The Ohio also sank, but all 16 of its crew members escaped with their lives.

The location of the sunken Ironton remained a mystery for more than 120 years. In 2017, a breakthrough came when researchers from the marine sanctuary located the Ohio, generating new interest in both shipwrecks.

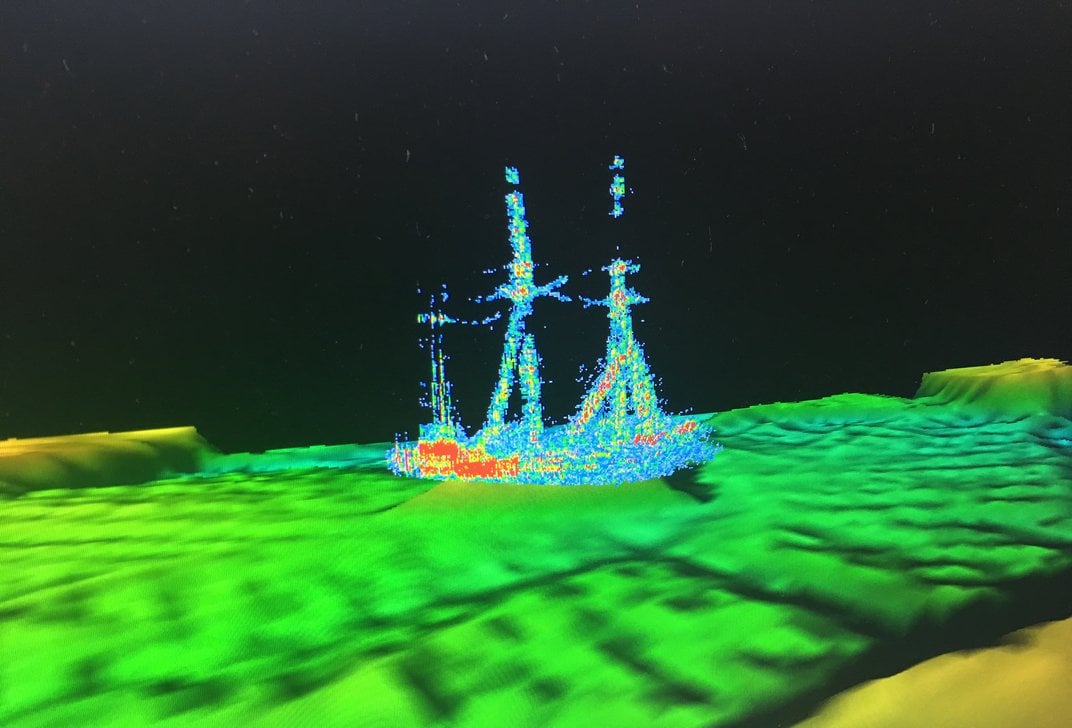

Per the New York Times’ Michael Levenson, researchers from the marine sanctuary partnered with Ocean Exploration Trust, the group known for finding the Titanic in 1985, and embarked on a mapping expedition. Using sonar imaging, they were able to pinpoint the Ironton’s location in 2019. Since then, researchers have been mapping out the “magnificently preserved” remains, according to the statement from NOAA.

“It is hard to call it a shipwreck,” Gray tells the Times. “It’s a ship, sitting on the bottom, fully intact, and the lifeboat there, literally, is a moment frozen in time.”

Most of the sanctuary’s other wrecks are not in such good condition. The sanctuary allows visitors to explore them through dives and snorkeling. NOAA says that the sanctuary will place a buoy to “mark the shipwreck’s location and help divers visit the wreck site safely.”

Now that the Ironton’s discovery has been announced, the researchers hope that it can serve as an educational tool.

“Archaeologists study things to learn about the past, but it’s not really things that we’re studying; it’s people,” Gray tells the AP. Examining the ship’s remains—particularly the lifeboat—“reminds you of how powerful the lakes are and what it must have been like to work on them and lose people on them.”